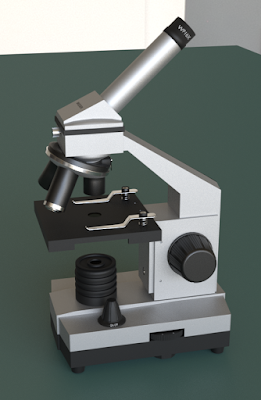

Microscope

Here we are. We have finally arrived at our destination. Some of us with noticeably fewer limbs and less enthusiasm than when we set out, but nevertheless, we've made it. We are now standing at the door to a super secret facility where the top minds from all over the world are working on the best— Oh, who am I trying to fool here, you have all seen the title image. It's a microscope, alright? And a bloody complicated one at that.

I know what you are thinking. The microscope couldn't have possibly been selected by the same rigorous approach as the previous objects. Who has a microscope at home at this day and age? Well, I do. It was a gift, and I am very fond of it, and I'm definitely going to start using it, some day. It is in fact in my daily plan: item 2487, right after "Learn Portuguese".

I know what you are thinking. The microscope couldn't have possibly been selected by the same rigorous approach as the previous objects. Who has a microscope at home at this day and age? Well, I do. It was a gift, and I am very fond of it, and I'm definitely going to start using it, some day. It is in fact in my daily plan: item 2487, right after "Learn Portuguese".

Excuses aside, it was an ideal candidate for my next project. I got quite cocky with my modelling abilities and I needed something to put me in my place. In that respect it was a remarkable success. But strangely enough, I don't remember as much about creating it as I do about the other ones. Something to do with self-preservation, probably.

I do remember that I was working on it, on and off, for about 3 weeks. Which is by far the longest project of them all. I realized quite early that I had to keep things well ordered if I didn't want to drown in all those "Cube.126's" and "Plane.42's" in the scene. With everything named appropriately it was much easier to navigate the maze later on. But if you do this, at some point you will start asking people questions like, "What would you call this metallic bit here, no, not that one, the other one that holds the two thingies on top of that big one?" And they'll look at you as if you just lost your marbles and should start looking for them immediately.

But even if you persist and name everything, there are still plenty of pieces that need to be grouped together if you don't want to spend an hour searching for a particular screw to duplicate. And you don't necessarily want to join the objects, because you may want to edit them later. Blender has a neat feature for this very purpose: object parenting. It does exactly what it says on the box — a selected object will become the parent and others will be its children. Afterwards, when you manipulate the objects they will stick together. You just need to think ahead about the overall structure of your object. And what was it that I didn't do? Exactly. As a result, I spent way more time shuffling things around than necessary (and healthy).

Eventually, with the architectural stuff all sorted out, I was able to dive deeper into the modelling. The large parts of the microscope didn't pose many problems except for one: bevel. I still haven't figured out how to use it in conjunction with other modifiers. I also haven't studied all its possible settings — my approach to this one was "press everything until it doesn't look terrible anymore". In the end, I was able to produce one of three possible outcomes: a) nothing changed, b) everything changed but not the way I wanted, and c) I created something that would make Frankenstein's monster blush.

Nevertheless, I kept progressing steadily. I created the base, reworked it a few times, started modelling the neck, realized I made the base all wrong, deleted it and started again. In the depths of despair I resorted to the one thing that had saved me before. My precious measuring tape. It certainly got to see a lot of action in this project. But for whatever reason, it decided to abandon me. Do you know how they say, "look before you leap"? Whoever coined that phrase must have been

really good at looking because I could take the measurements twenty times and still manage to get it wrong, somehow. I swear there are

gnomes living in my Blender and they are fiddling with it when I'm not looking. Nasty little

buggers.

After a lot of tweaking and gnome exorcising, I had the rough outline of the microscope finished, and I began working on the details. If I had a critter problem before, now the Devil himself decided to make an appearance. I had imagined that all those cog wheels and springs and what have you will be difficult, but boy, was I wrong. I think I spent a whole evening just on the focus knob, trying to get the teeth right. And then I had to watch several tutorials on how to make indentations in your mesh without screwing it up completely. And all that just because I needed to screw IN the actual screws. Which most people will miss anyway — as well as the tiny springs in the metallic holders of the central plate. But they were fun to make, and I never modelled anything so small before, so it was good practice.

When the time had come to give the microscope a shiny new coat, I decided that after all the gruesome modelling work it deserved the best materials I could put together. Luckily for me, Blender Guru had posted a tutorial on PBR materials shortly before that, so I was able to use his node setup with little to no hassle (you can watch the tutorial here if you like). As a result, my microscope has fresnel, and all that jazz. Do I have any clue what a fresnel is? Sure! Sort of... The truth is that I'm still struggling with half of the concepts he mentioned in the video so it may take some time before I'm truly comfortable with using them.

As it happens, however, I might not need them in the foreseeable future because I'd like to experiment with less realistic art styles. My ultimate reason for using Blender is to be able to create game assets. And as lovely as the realistic ones look, they take forever to make — which is impractical at best if you want to create a game on your own. This is why, starting from next week, I'm going to make a few low-poly scenes, just to get the hang of things. I really hope that I'll be able to produce some nice looking renders in reasonable time, because from what I've seen so far, this is an art style I could seriously enjoy.

Comments

Post a Comment